In this fourth of a series of blogs reflecting on previous enhancement themes projects, Grace Smith, Printed Textiles Technician and Community Engagement Lead in the School of Textiles & Design reflects on supporting students to develop tactile skills and connect with the community during the Covid pandemic.

The year is 2021 and the Covid-19 Pandemic is having a significant impact worldwide (WHO, 2020). Globally, universities, move their face-to-face teaching online allowing higher education to continue (Viyayan, 2021, Tsang et al., 2021).

I’m Grace Smith, a Printed Textile Technician working for the School of Textiles and Design (SoTD) at Heriot-Watt University. Finding myself working from home instead of my wonderful workshop and developing new ways to teach hands-on process via digital means in students’ homes.

The What?

A key area I had been involved with pre-pandemic, was providing school and community workshops on and off-campus. These opportunities for in-person engagement had (understandably) dried up. With these opportunities no longer possible, I was keen to explore other avenues and so the student-led digital workshop was born.

The mini project had three aims:

- To provide student opportunities, that were being lost due to Covid-19, in facilitating and taking part in workshop and recruitment activity in addition to collaborating with peers in extra-curricular activity

- To connect with the community by providing a creative online workshop and accompanying materials packs

- To promote the School of Textiles and Design (SoTD) to a wider audience whilst engaging with recruitment activities

Three students from the BA (Hons) Design for Textiles programme were recruited via an application process to create the digital workshop.

Three students from the BA (Hons) Design for Textiles programme were recruited via an application process to create the digital workshop.

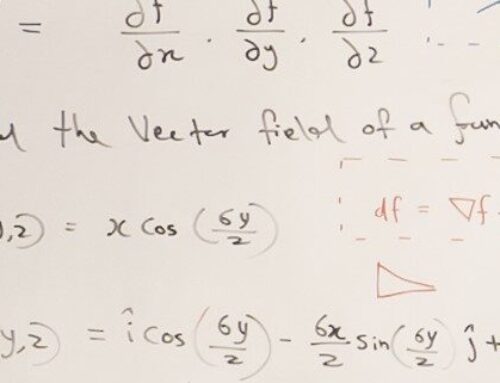

Student facilitators created a video workshop to teach others how to block print a tote bag. The students created all the video content to show participants how to create a block printed tote bag in six steps. They also created material packs with all the items needed to create the tote bag. The video not only showed how to create the bag but also highlighted students’ work and promoted study at SoTD.

The finished video and materials packs were distributed to schools around the UK, approximately 140 learners from a range of year groups. Ethics approval was received to collect evaluative data from the student facilitators, teachers and learners.

The Why?

A deep dive into the literature, further cemented my initial understanding, highlighting why engagement (both in-person and online) is important to the student and university.

University and Community Benefits:

- Engaging with the public allows both parties to learn from each other and build trust, understanding and collaboration (Duncan & Manners, 2012).

- Community ties can have a positive effect on student recruitment and research capacity (Franklin, 2008).

Student Benefits:

- Providing students with ‘real world’ learning experiences (Laur, 2013) increasing employability and experience (Brewis, 2011).

- Students express a preference for doing rather than listening and are motivated by solving real-world problems (Lombardi and Oblinger, 2007).

- Applying skills and knowledge learnt via formal studies and can lead to ownership of their own learning (Lai and Smith, 2018).

- Nurture belonging through involvement in extra-curricular activities (Abernathy & Vineyard, 2001), ultimately enriching the overall student experience (Ferrera et al. 2018).

Impact and Evaluation

Impact and Evaluation

As part of the process, I gained Ethics Approval and collected data from the student facilitators, school learners and teachers. This provided insight into participant experiences of the project.

All the Student Facilitators completed a questionnaire and commented they felt there had been the same number of opportunities for work experience, competitions and funding as pre-pandemic times. However, the type of opportunities had changed with more ‘hardship grants’, in addition to online activities. There also seemed to be more competitions available, possibly to keep connection with businesses and organisations during this time.

Ultimately, what they missed the most was in-person connection and in-person internships. One student commented that it was beneficial to connect with staff and their peers outside of formal activities and share their contributions ultimately making the content they provided with the online workshop much stronger. Another student commented they had different skills and ideas to contribute, and it was beneficial to see different points of view and learn from each other. The most beneficial aspects of the opportunity were personal connection, learning about how to put together a digital workshop, in addition to confidence building.

In the initial stage, the digital workshop and materials pack was sent to five schools, with four in Scotland and one in England.

The teachers that responded to the questionnaire commented that they found the resources and ‘clear and engaging’ instructions the most useful part of the workshop, with most of the learners, who were provided with a survey, enjoying the designing and printing part of the workshop the most. Around 80% of the learners that participated, had not heard of Heriot-Watt University, School of Textiles and Design before taking part.

Benefits to others

Benefits to others

I believe there are two key takeaways from the mini-project:

- Digital resources make engagement possible to a wider audience, with potential for national and even global participation and promotion.

- Involving students as workshop facilitators benefits the students, the university and the community

As Furco (2010) sums up, real-life can be messy and complex, and offering these experiences can provide excellent opportunities for strengthening the student’s education whilst also giving back to the community. Two things I strive to do more of through my job.

View the final digital workshop here or by contacting grace.smith@hw.ac.uk.

Image credits: All (c) Grace Smith

References

Brewis, G., 2011. A short history of student volunteering. London: Volunteering.Duncan, S. and Manners, P. (2012) “Embedding Public Engagement within HE: Lessons from the Beacons for Public Engagement in the UK” Higher Education and Civic Engagement. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Chapter 13, pp.221-240. doi:10.1057/9781137074829.

Ferrara, M., Talbot, R., Mason, H., Wee, B., Rorrer, R., Jacobson, M. and Gallagher, D. (2018) ‘Enriching Undergraduate Experiences With Outreach in School STEM Clubs’, Journal of college science teaching, 47(6), pp. 74–82.

Franklin, N. (2008). The land-grant mission 2.0: Distributed regional engagement (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania). https://www.proquest.com/docview/304494017?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

Furco, Andrew (2010) The Engaged Campus: Toward a Comprehensive Approach to Public Engagement, British Journal of Educational Studies, 58:4, 375-390, DOI: 10.1080/00071005.2010.527656

Lai, K., & Smith, L. (2018). University Educators’ Perceptions of Informal Learning and the

Ways in which they Foster it. Innovative Higher Education, 43(5), 369-380.

Laur, D., 2013. Authentic learning experiences: A real-world approach to project-based learning. Routledge.

Lombardi, M.M. and Oblinger, D.G., 2007. Authentic learning for the 21st century: An overview. Educause learning initiative, 1(2007), pp.1-12.

Tsang, J.T., So, M.K., Chong, A.C., Lam, B.S. and Chu, A.M., 2021. Higher education during the pandemic: The predictive factors of learning effectiveness in COVID-19 online learning. Education Sciences, 11(8), p.446.

Vijayan, R., (2021). Teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A topic modeling study. Education Sciences, 11(7), p.347.